By: Carter Coudriet, GMU Student Contributor

Executive Summary

Thanks to its massive population and economy, China houses the world’s highest national electricity demand. In servicing this demand, China produces the world’s largest sum of greenhouse gas emissions, a figure that will continue to grow as China’s per capita electricity usage soars. While the C.C.P. has implemented an emissions trading scheme and other pro-transition policies, a fully carbon-neutral scenario would sacrifice the security that coal bestows. A coal-free future would also require China to overhaul its regulatory and trade strategies.

However, diversified options exist for China to facilitate an inclusive and secure green energy transition. Some of the most robust policy recommendations available lie squarely in the C.C.P.’s control, taxing carbon to shifting public financing. Others involve reimagining how China engages with the global energy market—and potentially with its great power rivals.

The United States must therefore craft its own strategic responses to China’s renewable electricity growth. As great powers seek influence while maintaining energy security, this brief presents ways the U.S. can compete or collaborate with China in green power proliferation.

Introduction

The People’s Republic of China (“China”) presents a complex green energy development challenge. As its economy continues to grow, China will generate 10.2 petawatt hours (“PWh”) in 2030, up drastically from 7.6 PWh in 2020.[i] Energy security will remain a top concern for the Chinese Communist Party (“C.C.P.”), with coal presenting a pragmatic yet dirty solution to its needs.[ii] This coal reliance could worsen China’s heightening contribution to climate change; it is already the world’s highest emitter of greenhouse gases, even with less than half the per capita electricity usage of Americans.[iii] Chinese President Xi Jinping has pledged radical change in the country’s power sector, aiming to hit peak emissions in 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060.[iv]

As Chinese energy adapts to the nation’s economic and emissions goals, experts highlight numerous avenues for policy development, many of which implicate U.S. trade and security. With its extensive electricity grid and ample natural resources, China can piggyback efficiency and footprint improvements onto its existing infrastructure. China can further disincentivize its continued reliance on coal by adapting its budgeting and educational capacities. Of most significance to the West, China could reorient its development efforts around proliferating and innovating global green energy supply, and it could liberalize elements of its foreign investment strategy to form deeper international partnerships. In each of these areas, the U.S. faces an opportunity to invest in the global energy future, either in tandem or in contest with the C.C.P.

As this briefing explores, the United States must consider routes toward preserving its energy, economic, and environmental interests amid China’s transition. This paper first provides background on China’s economy, environmental impact, and relevant relationships with the United States. Second, this briefing explores the current policy landscape pertaining to China’s energy transition. Given that landscape, this analysis introduces policy options available to the C.C.P. After listing policies that China can enact unilaterally, this briefing will focus on U.S.-relevant policies and on America’s role in those policies’ deployment. To close, this brief will draw from its policy pathways to provide recommendations for each nation’s approach.

Background: China’s Electric and Economic Power

China is one of the world’s largest economies. The most populous nation on earth,[v] China boasts a GDP of $17.7 trillion USD, second only to the United States.[vi] China also houses significant natural resource endowments, including the sixth-longest waterways of any country[vii] and 37.7% of the world’s rare earth metal reserves.[viii]

Fueling that economy and exploiting those resources requires abundant electrical power. China generated 8,459.9 terawatt hours (“TWh”) of electricity in 2021, more than double the United States’ generation.[ix] That capacity has room to grow; while the nation reached practically universal electrification in 1997,[x] China’s generation per capita is less than half that of the United States.[xi]

To achieve energy security while meeting its huge demand, China maintains expansive domestic infrastructure. China’s power grid sector serves 589.07 million customers, with two state-owned firms holding a combined 95% share in electricity and transmission.[xii] China’s grid loses 5.26% of its electricity in transmission,[xiii] on par with the United States’ grid.[xiv]

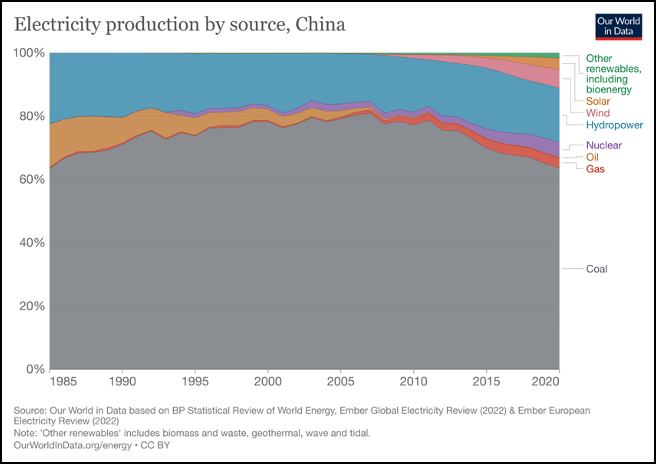

That grid, and China’s overall power sector, is a significant driver of both green integration and carbon emissions. China leads the world in green energy capacity[xv] and is a net exporter of renewable energy products.[xvi] Chinese President Xi Jinping has promised that China will reach peak emissions this decade and will be carbon neutral by 2060.[xvii] However, China’s world-topping annual greenhouse gas emissions exceed 10 billion tons, more than four billion tons ahead of the U.S.[xviii] As shown in Image 1, coal originates more than 60% of China’s power.[xix]

Trade is also crucial to China’s energy supply and thus represents a challenge to China’s energy security. China’s net imports of energy reached 15% in 2014.[xx] Its world-leading supply of imported liquified natural gas draws largely from Western nations like Australia and the United States.[xxi] China has pursued “a stable international order for the pragmatic satisfaction of its energy needs;”[xxii] between 2014 and 2017, major Chinese banks lent $25.7 billion in electricity-related loans as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (“BRI”).[xxiii]

Though not a part of BRI, the United States will likely play an influential role in China’s green energy transition, either as friend or foe. In 2009, the great powers launched the U.S.-China Clean Energy Research Center and reached “a significant set of new agreements […] including on electric vehicles, energy efficiency, renewable energy, clean coal, and shale gas.”[xxiv] In 2020, the U.S. sent more than $9 billion in FDI to China across all industries.[xxv] However, as tensions build between the nations, the U.S. has taken aim at Chinese trade practices, including “accusing China of ‘forcing’ technology transfer by US firms seeking to invest in China.”[xxvi]

Image 1: China’s Electricity Mix

Image Source: Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser, and Pablo Rosado, “China: Energy Country Profile.”

Literature Review: Policies and Practices

China historically has shown an immense capacity to implement drastic energy transitions. Observing the C.C.P.’s eradication of electricity poverty through the tripartite transition framework developed by Aklin et al.,[xxvii] early party leaders successfully built the political will, institutional capacity, and local accountability necessary to both proliferate and use energy infrastructure. Given the global isolation of early Communist China, the C.C.P. prioritized energy security through “indigenous development in cities and the countryside,”[xxviii] a process that they fostered by building “a set of institutions that were able to guide rural electrification.”[xxix] Even when national Maoist leadership underperformed, “the governing committees and councils […] in the villages and townships of rural areas constantly faced popular pressure to improve rural electrification,” and projects succeeded thanks to “an early decision to share the cost of rural electrification among multiple levels of government.”[xxx]

Much of this capacity for effective transitions endures today. Its authoritarianism enables the C.C.P to utilize “mandatory policy instruments [that set] up stringent top-down plans, targets, and penalty systems for localities or organizations to follow or comply.”[xxxi] Compared to more participatory forms of government, China’s model is “more effective in delivering policy outputs without lengthy political debates or strong lobbying.”[xxxii] Locals still have some accountability tools at their disposal; Huang et al. point to the “defensive participation” employed by the villagers of Qiaoxiang—in this case, complaining in the media— to “provide[] the government with a clear signal of the need for policy adjustment” when implementing solar energy.[xxxiii]

Xi’s commitment to carbon neutrality by 2060 conveys the importance of green electricity to the C.C.P., which has implemented some pro-transition policies. In 2011, China implemented feed-in tariffs (“FiT’s”) in the solar sector, helping to cultivate the solar market and contributing to an increase in solar generation from fewer than 20 TWh in 2011 to more than 170 TWh in 2018.[xxxiv] China has built 30,000 km of “ultra-high-voltage” transmission lines[xxxv] and announced in 2015 that it would “phase out selected fossil fuel subsidies.”[xxxvi] Two of its most pronounced moves came in 2021: the implementation of the world’s largest emissions trading scheme (“ETS”),[xxxvii] and the promise to “not build new coal-fired power projects abroad.”[xxxviii]

Despite this progress, the world’s largest emitter faces substantial obstacles to embracing green energy more fulsomely. Experts observe a gamut of issues with China’s transition, broadly attributable to four main categories: cost, security, regulation, and trade.

A. Cost Issues: The affordability of coal impedes renewables’ business case. Municipal government leaders from China’s Greater Bay Region, when interviewed by Wang et al., claimed that “coal-fired power units are in general cost-competitive as compared with other types of power units.”[xxxix] China abets coal’s cheapness through public funding; since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, China has “committed at least USD 45.15 billion to coal,” compared to “$20.51 billion supporting clean energy,” per Columbia-cosponsored EnergyPolicyTracker.org.[xl]

Meanwhile, emissions-cutting technology remains expensive, even given China’s efforts to mature these markets. China’s solar FiT’s have improved the business case for the renewable form of energy, yet “the existing Chinese feed-in tariffs policy may not be able to support the rapid development of renewable energy.”[xli] China has bolstered some elements of its grid, yet “wind power and solar power[] is heavily dependent on the natural environment, and grid availability is the biggest obstacle constraining their development.”[xlii] The two massive state-owned grid enterprises have also not pursued important innovations, like expanding renewable-integrated connections or cutting transmission losses.[xliii]

Moving beyond coal carries additional societal costs in China. Clark and Zhang estimate that China’s coal subsidies might far outpace China’s coal-related tax revenues over the next decade if China commits to Xi’s neutrality goal, rendering coal “likely a net fiscal drain on China’s public finances.”[xliv] They also point to weighty disruptions in employment, “with jobs losses from mining alone expected to exceed 1.1 million by 2035.”[xlv]

Even technology that would hypothetically extend the shelf-life of coal—such as carbon capture, utilization, and storage (“CCUS”) usage that would reduce emissions—is of debatable value. Since coal might be wholly retired in the carbon-neutral-2060 scenario, the timeline for the usefulness of CCUS is shrinking, “even if CCS technologies reach commercial scalability.”[xlvi]

B. Security Issues: Supporting the world’s largest population, especially in a contested geopolitical climate, leads China to prioritize energy security over green energy. Coal, along with hydropower, is a chief source of baseload power[xlvii] and thus an essential component of China’s supply-side strategy. China has the world’s largest endowment of coal reserves and thus maintains “over half of global coal-fired power generation capacity.”[xlviii] “Almost all” of Wang et al.’s interviewees “expressed concern that the closure of local coal-fired power units may pose challenges with respect to energy security.”[xlix]

However, China’s under-diversification also threatens its security, with different regions facing varied challenges. While electric grid density is high in coastal areas like Shanghai, “The inland provinces with abundant energy resources, Qinghai, Xinjiang, and Inner Mongolia, had the lowest power grid density,” which creates “poor liquidity of energy resources between regions.”[l] Asymmetry in regional generation-versus-grid hurts resource-poor coastal regions as well; the East China Power Grid is dependent on external generation and lacks robust local generation infrastructure, leading to “insufficient peak regulation capacity.”[li]

C. Regulation Issues: The current regulatory environment surrounding Chinese green energy hinders the growth of green energy. China has implemented some carbon mitigation policies, yet the C.C.P. has not adopted ambitious measures like a carbon tax.[lii] According to the International Energy Agency, China’s new ETS, while ambitious and helpful, provides “very limited encouragement for fuel switching to non-fossil sources.”[liii] The scheme emphasizes improving the emissions intensity of coal and gas, rather than actually capping emissions.[liv]

Further, legislative vagueness allows for corruption and coal-friendly influence. Shen and Jiang observe that “Some regulations and targets are intentionally designed with ambiguity,” which “leav[es] local political leaders with significant autonomy to decide what to be implemented sincerely or emblematically.”[lv] These leaders often balk at full implementation of green policies, given “polluters’ contribution to the local economy and close links with local bureaucratic elites.”[lvi] While the public can gripe in the media, given the authoritarian nature of China’s government, communities cannot wield heavy influence without “a greater diversity of channels of expression such as community workshops and digital participation platforms.”[lvii]

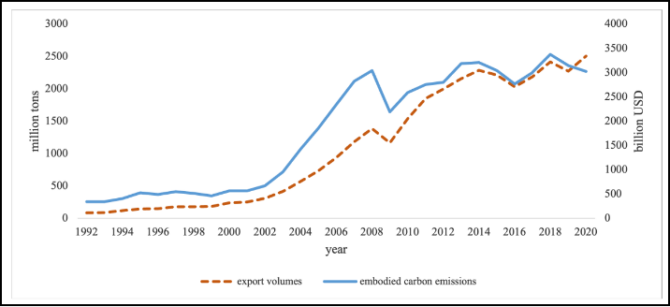

D. Trade Issues: China’s approach to trade worsens its environmental impact. Chinese exports embed more than 2 billion tons of emissions, as shown in Image 2. BRI contributes to growing emissions, as “the Belt and Road Initiative increase[s] the carbon emissions embodied in most of the industries’ exports.”[lviii] The C.C.P., a major player in great power competition, also employs a series of policies and practices that discourages green trade, from its “42 per cent anti-dumping duties on German, Italian, and Spanish solar-grade polysilicon,”[lix] to its alleged overall practice of “‘forcing’ technology transfer by US firms seeking to invest in China.”[lx]

These issues, along with the others discussed, dampen the prospective market for foreign investment in China’s green energy transition. Keeley and Matsumoto identify the relative importance of 18 determinants for developing nations’ ability to attract foreign direct investment (“FDI”) in the solar and wind energy sectors.[lxi] Of the top six factors, the issues discussed in this section cover four: priority access to the grid (i.e., grid density issues in resource-rich regions), natural resources (i.e., low resources in grid-rich regions), administrative procedure (i.e., ambiguous regulations and targets), and feed-in tariffs (i.e., insufficient incentives for solar).

Image 2: Emissions Embedded in Chinese Exports

Image Source: Jiajia Li et al.,“Heterogeneous Driving Factors of Carbon Emissions Embedded in China’s Export: An Application of the LASSO Model,” 7.

Policy Options: Opportunities and Potential Role of the United States

The literature portrays China’s green energy transition as a complex, yet not unsolvable, policy quagmire. Options exist for the C.C.P. to augment its infrastructure, disincentive dirty energy, and promote equitable transitions. By leveraging its economic strength, natural resources, and authoritarian efficiency, China has the capacity to lead the global green energy transition.

This capacity of China is both a challenge and an opportunity for the United States. The U.S. is interested in China undergoing its transition, given the massive impact China’s emissions will have in the fight against climate change. As China pursues its transition, the United States still must ensure its own electric, environmental, and economic security. Its options include pushing China to increase its dedication to its transition, undercutting China’s efforts to influence other nations’ energy use, and potentially partnering with China when appropriate.

Crucially, some policy approaches that the U.S. might use with conventional developing nations are unlikely to work in China. The U.S. is likely unable to use capital or technical expertise to reform China’s governmental capacities or to liberalize its markets. Trading funding for influence is not as strong an option in China as in less developed states, where agencies like USAID or the Development Finance Corporation (“DFC”) can generate soft power.[lxii]

This section will first explore four templates that China could pursue without any U.S. role. It will then explore four approaches with potential U.S. involvement or responses.

A. Unilateral Chinese Options: Some of China’s most top options entail either sectors where China is already a leader, or where foreign involvement would undermine security:

1. Tax Structure Catch-Up—China could consider implementing a carbon tax, along with replacing its intensity-based ETS with pure cap-and-trade. The IEA estimates that this would not add any system costs yet would drastically decrease the proportion of coal in the nation’s energy mix, cutting about 400 TWh of coal power by 2030.[lxiii] Li and Yao concur that the “effect of carbon emission reduction brought by mixed policy is better than that from single policy.”[lxiv]

2. Greener Public Financing—China could consider rapidly reallocating public coal finance toward further subsidizing FiT’s and auctions for renewables. Delina points to government budgets as significant drivers of energy transitions.[lxv] The billions of dollars China uses to subsidize coal could amplify China’s successes in renewable FiT’s and bolster its use of auctions in low-resource regions, like its 2008 “Shandong Province one million rooftops sunshine plan.”[lxvi] It could also fund smaller-scale hydro that can take advantage of China’s abundant waterways; China could scale small, less-disruptive plants for “$750 to $2,500 per kW installed capacity.”[lxvii] The C.C.P. could increase buy-in from influential dirty energy firms by giving them advantages in auctions or discounts on FiT’s, though this illiberal approach carries disadvantages.

3. Improving Asymmetries—Given its sway over state-owned grid companies and other energy firms, the C.C.P. could focus business leaders on regional grid security. Grid modernization funding in China will already reportedly hit $896 billion by 2026.[lxviii] By generating carbon tax revenue, China could provide even more funding toward expanding grid connections in resource-rich areas, along with solar and small-scale hydro generation in resource-poor regions.

4. Job Re-Training—China could pursue human capital development for coal-connected workers. Given the job losses expected from ditching coal, China could establish a “National Renewable University” network that re-trains workers in energy-related jobs, such as servicing renewable infrastructure. Given China’s historical emphasis on local participation, each province could establish a branch, which would draw from graduates’ future earnings for sustainable funding.

B. Two Birds, One Stone: China could consider more approaches that augment its existing infrastructure. The U.S. could partner with China or drive further competition.

1. Bolster Grid Efficiency—China could invest in researching and developing even more efficient transmission. China reportedly plans to build $34 billion worth of ultra-high-voltage lines by 2026.[lxix] By finding more ways to preserve efficiency, Chinese innovators could ensure that more energy reaches the customer, reducing the number of generation facilities required and thus decreasing the levelized cost of energy.[lxx]

2. Salvage Coal—China could reduce the upper bound of coal emissions by investing in rapid CCUS deployment. Tang et al. estimate that large-scale CCUS deployment will cost $83 billion annually by 2050.[lxxi] To incentivize prompt investments that would make CCUS deployment useful in a pre-carbon-neutral scenario, China could craft clear timelines for when coal plants must be CCUS-equipped. It could also employ creative finance-attracting techniques like those used by India in wind proliferation, including accelerated write-offs.[lxxii]

U.S. Options: The U.S., which sent more than $9 billion in FDI to China in 2020,[lxxiii] could work with Chinese firms to amplify innovation in transmission lines and CCUS. The U.S. would benefit from curing its own inefficiencies and from preserving a lower-emission form of coal usage while it transitions. Efficiency-building in China’s resource-poor regions may also be well-suited for FDI; per Pan et al., “FDI quality plays a significant role in promoting China’s energy efficiency in the coastal and inland areas, but its role in the inland area is significantly greater.”[lxxiv]

However, given American allegations regarding the C.C.P.’s forced technology transfers in other industries, the U.S. could also consider innovating in these sectors without Chinese involvement. While this route provides less funding for China’s important energy transition, it preserves the efficacy of American intellectual property. It also potentially gives the U.S. goods to export to its own trade partners, competing with China’s renewable products industry.

C. Big Tent: China could pursue green changes to its development efforts. The U.S. could affirm China’s efforts by boosting imports, or it could strengthen its own trade network.

1. Bolder Pledges—Building on its promise not to build foreign coal plants, China could commit to advancing green energy development in BRI nations. Using a similar model to the Japan-Vietnam Rare Earth Research and Technology Transfer Centre,[lxxv] China can share FDI and technology with rare-earth-metal-rich trade partners, potentially birthing a network of China-aligned developing nations that, like China,[lxxvi] become renewable product exporters.

2. Recruiting Women—Per Li et al., “women’s political empowerment contributes to the reduction in embodied carbon emissions,” and “governments should facilitate and encourage women to take high technology positions.”[lxxvii] The C.C.P., itself with less than one-third women membership,[lxxviii] could create a “Belt and Road Women’s Leadership Summit” and require gender inclusivity on all its domestic and recipient energy boards.

U.S. Role: As an economic powerhouse itself, the U.S. can incentivize China-led growth of green manufacturing by buying goods from BRI beneficiaries of Chinese technology sharing. It can likewise join forces with China to expand the role of women in global energy leadership.

However, the U.S. likely would not consider Chinese leadership in green energy trade to be in Americans’ interest. The U.S. could use its own agencies to build green manufacturing capacity in its own FDI recipients, as DFC did through debt financing to First Solar in India.[lxxix]

Commentary & Recommendations

This research brief has explored the past and present policies that shape China’s energy transitions, first toward electrification and currently toward renewables. After diagnosing cost, security, regulatory, and trade-related issues with those policies, this paper presents eight options—including four that could prompt U.S. involvement or intervention—for China to consider as it seeks peak emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality in 2060.

While each of these strategies could facilitate China’s green energy transition, the most impactful recommendations are likely “Tax Structure Catch-Up,” “Greener Public Financing,” “Improving Asymmetries,” and “Bolder Pledges.” These address systemic and high-emissions issues with China’s carbon footprint; a combination of these policies would cut hundreds of TWh of dirty energy, bolster grid connections to renewables, and strengthen Chinese global leadership.

Whether or not the C.C.P. holds the political will to pursue these policies in the short term remains to be seen. Tellingly, three of these four policies are already totally within China’s control. After China’s reported push to change language in the Glasgow Climate Pact from a call to “phase-out” coal to “phase-down” coal, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesman asserted that “China has already made ‘enormous efforts’ in controlling coal consumption.”[lxxx] China’s ambition for future green energy will evidently yield to its desire for present energy security.

The United States should therefore seriously consider this brief’s leadership-building recommendations, which would seize the present opportunity to fortify American global influence. When appropriate, the U.S. can leverage its aforementioned research relationship with China to collaborate, such as in unscaled technology like CCUS or in global women’s empowerment. However, given existing trade tensions and China’s human rights abuses,[lxxxi] the U.S. could strengthen its bargaining position against China and build global alliances by championing its own “Bolder Pledges,” “Salvage Coal,” and “Bolster Grid Efficiency” analogs.

China is a formidable competitor to the U.S. in green electricity leadership. The C.C.P. holds huge advantages, from its authoritarian efficiency to its powerful green energy product industries.[lxxxii] Nevertheless, the massive mobilization of FDI and research investment could propel the U.S.’s pitch for global renewable electricity leadership.

[i] IEA, “Executive Summary – Enhancing China’s ETS For Carbon Neutrality: Focus On Power Sector – Analysis.”

[ii] Peng Wang et al., “Explaining the Slow Progress of Coal Phase-Out: The Case of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Region,” 3.

[iii] Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser, and Pablo Rosado, “China: Energy Country Profile.”

[iv] United Nations, “China Headed towards Carbon Neutrality by 2060; President Xi Jinping Vows to Halt New Coal Plants Abroad.”

[v] United States Census Bureau, “International Database.”

[vi] The World Bank, “Gross Domestic Product 2021.”

[vii] Central Intelligence Agency, “Country Comparisons—Waterways.”

[viii] BP, “BP Statistical Review of World Energy,” 59.

[ix] Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser, and Pablo Rosado, “China: Energy Country Profile.”

[x] Michaël Aklin et al., Escaping the Energy Poverty Trap: When and How Governments Power the Lives of the Poor, 157.

[xi] Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser, and Pablo Rosado, “China: Energy Country Profile.”

[xii] Bai-Chen Xie et al., “The Scale Effect in China’s Power Grid Sector from the Perspective of Malmquist Total Factor Productivity Analysis,” 1; State Grid Corporation of China, “Corporate Profile”; China Southern Power Grid, “Company Profile.”

[xiii] Statista Research Department, “China: Electricity Transmission Losses 2021.”

[xiv] U.S. Energy Information Administration, “How Much Electricity Is Lost in Electricity Transmission and Distribution in the United States?”

[xv] Madhumitha Jaganmohan, “Leading countries in installed renewable energy capacity worldwide in 2021.”

[xvi] Shuai Jing, “China’s Renewable Energy Trade Potential in the ‘Belt-and-Road’ Countries: A Gravity Model Analysis,” 1026.

[xvii] Smriti Mallapaty, “How China Could Be Carbon Neutral by Mid-Century,” 482.

[xviii] Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser, and Pablo Rosado, “China: Energy Country Profile.”

[xix] Ibid.

[xx] World Bank, “Energy Imports, Net (% Of Energy Use).”

[xxi] Victoria Zaretskaya and Faouzi Aloulou, ”As Of 2021, China Imports More Liquefied Natural Gas Than Any Other Country.”

[xxii] Jinh Zhang, “Oil and Gas Trade Between China and Countries and Regions Along the ‘Belt and Road’: A Panoramic Perspective,” 1112.

[xxiii] Lihuan Zhou et al., Moving the Green Belt and Road Initiative: From Words to Actions.

[xxiv] Joanna I. Lewis, “Toward a New Era of US Engagement with China on Climate Change,” 174.

[xxv] Bureau of Economic Analysis, “International Data: Direct Investment and MNE.”

[xxvi] Weihuan Zhou, Qingjiang Kong, and Huiqin Jiang, “Technology Transfer Under China’s Foreign Investment Regime: Does the WTO Provide a Solution?” 456.

[xxvii] Michaël Aklin et al., Escaping the Energy Poverty Trap: When and How Governments Power the Lives of the Poor, 61.

[xxviii] Id., 159.

[xxix] Id., 160.

[xxx] Id., 161.

[xxxi] Wei Shen and Dong Jiang, “Making Authoritarian Environmentalism Accountable? Understanding China’s New Reforms on Environmental Governance,” 43.

[xxxii] Id., 43-44.

[xxxiii] Ping Huang, Vanesa Castán Broto, and Linda Katrin Westman.,“Emerging Dynamics of Public Participation in Climate Governance: A Case Study of Solar Energy Application in Shenzhen, China,” 314-315.

[xxxiv] Qiang Tu et al., “Achieving Grid Parity of Solar PV Power in China- The Role of Tradable Green Certificate,” 1-2.

[xxxv] Shuzhu Shi et al., “Scattering Characteristics of Ultra-High-Voltage Power Lines in Spaceborne SAR Images,” 13.

[xxxvi] Laurence L. Delina, Accelerating Sustainable Energy Transition(s) in Developing Countries: The Challenges of Climate Change and Sustainable Development, 109.

[xxxvii] IEA, “Executive Summary – Enhancing China’s ETS For Carbon Neutrality: Focus On Power Sector – Analysis.”

[xxxviii] Huaxia, “Full Text of Xi’s Statement at the General Debate of the 76th Session of the United Nations General Assembly.”

[xxxix] Peng Wang et al.,“Explaining the Slow Progress of Coal Phase-Out: The Case of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Region,” 7.

[xl] EnergyPolicyTracker.org, “China.”

[xli] Qiang Tu et al., “Achieving Grid Parity of Solar PV Power in China- The Role of Tradable Green Certificate,” 1.

[xlii] Bai-Chen Xie et al., “Measuring the Efficiency of Grid Companies in China: A Bootstrapping Non-Parametric Meta-Frontier Approach,” 1382.

[xliii] Id., 1381.

[xliv] Alex Clark and Weirong Zhang, “Estimating the Employment and Fiscal Consequences of Thermal Coal Phase-Out in China,” 1.

[xlv] Ibid.

[xlvi] Id., 2.

[xlvii] EME 807: Technologies for Sustainability Systems, “9.1. Base Load Energy Sustainability.”

[xlviii] Alex Clark and Weirong Zhang, “Estimating the Employment and Fiscal Consequences of Thermal Coal Phase-Out in China,” 1.

[xlix] Peng Wang et al.,“Explaining the Slow Progress of Coal Phase-Out: The Case of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Region,” 5.

[l] Fang Yang, Sheng Zhang, and Chuanwang Sun, “Energy Infrastructure Investment and Regional Inequality: Evidence from China’s Power Grid,” 2.

[li] Lingjun Xu, Da Sang, and Xiaohu Zhang, “Analysis of Influence of Large-Scale External Power on East China Power Grid,” 5.

[lii] Xiaoyu Li and Xilong Yao, “Can Energy Supply-Side and Demand-Side Policies for Energy Saving and Emission Reduction Be Synergistic?— A Simulated Study on China’s Coal Capacity Cut and Carbon Tax,” 1.

[liii] IEA, “Executive Summary – Enhancing China’s ETS For Carbon Neutrality: Focus On Power Sector – Analysis.”

[liv] Ibid.

[lv] Wei Shen and Dong Jiang, “Making Authoritarian Environmentalism Accountable? Understanding China’s New Reforms on Environmental Governance,” 45.

[lvi] Id., 44.

[lvii] Ping Huang, Vanesa Castán Broto, and Linda Katrin Westman.,“Emerging Dynamics of Public Participation in Climate Governance: A Case Study of Solar Energy Application in Shenzhen, China,” 315.

[lviii] Jiajia Li et al.,“Heterogeneous Driving Factors of Carbon Emissions Embedded in China’s Export: An Application of the LASSO Model,” 9.

[lix] Laurence L. Delina, Accelerating Sustainable Energy Transition(s) in Developing Countries: The Challenges of Climate Change and Sustainable Development, 116.

[lx] Weihuan Zhou, Qingjiang Kong, and Huiqin Jiang, “Technology Transfer Under China’s Foreign Investment Regime: Does the WTO Provide a Solution?” 456.

[lxi] Alexander Ryota Keeley and Ken’ichi Matsumoto, “Relative Significance of Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment in Wind and Solar Energy in Developing Countries – AHP Analysis,” 346.

[lxii] See e.g., Library of Congress, “S.2463 — 115th Congress (2017-2018).”

[lxiii] IEA, “Executive Summary – Enhancing China’s ETS For Carbon Neutrality: Focus On Power Sector – Analysis.”

[lxiv] Xiaoyu Li and Xilong Yao, “Can Energy Supply-Side and Demand-Side Policies for Energy Saving and Emission Reduction Be Synergistic?— A Simulated Study on China’s Coal Capacity Cut and Carbon Tax,” 7.

[lxv] Laurence L. Delina, Accelerating Sustainable Energy Transition(s) in Developing Countries: The Challenges of Climate Change and Sustainable Development, 126.

[lxvi] Id., 92.

[lxvii] Id. 51.

[lxviii] Muyu Xu and John Geddie, ”Analysis: To Tackle Climate Change, China Must Overhaul Its Vast Power Grid.”

[lxix] Ibid.

[lxx] Laurence L. Delina, Accelerating Sustainable Energy Transition(s) in Developing Countries: The Challenges of Climate Change and Sustainable Development, 121.

[lxxi] Haotian Tang, Shu Zhang, and Wenying Chen, “Assessing Representative CCUS Layouts for China’s Power Sector Toward Carbon Neutrality,” 11233.

[lxxii] Prem Kumar Chaurasiya, Vilas Warudkar, and Siraj Ahmed, “Wind Energy Development and Policy in India: A Review,” 347-348.

[lxxiii] U.S. Department of Commerce, “International Data: Direct Investment and MNE.”

[lxxiv] Xiongfeng Pan et al., “Influence of FDI Quality on Energy Efficiency in China Based on Seemingly Unrelated Regression Method,” 6.

[lxxv] Ichiko Fuyuno. “Japan and Vietnam Join Forces to Exploit Rare-Earth Elements.”

[lxxvi] Sarah Ladislaw and Philippe Benoit, ”Energy And Development: Providing Access And Growth,” 10.

[lxxvii] Jiajia Li et al.,“Heterogeneous Driving Factors of Carbon Emissions Embedded in China’s Export: An Application of the LASSO Model,” 14.

[lxxviii] Rui Guo, “China’s Communist Party Hits 96.7 Million, Boosted By Young And Educated.”

[lxxix] U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, “DFC Announces Approval to Provide up to $500 Million of Debt Financing for First Solar’s Vertically-Integrated Thin Film Solar Manufacturing Facility in India.”

[lxxx] Reuters, “China Rebuffs UK Criticism over Coal Move after Climate Summit.”

[lxxxi] See e.g., Library of Congress, “H.R.6256 – To ensure that goods made with forced labor in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China do not enter the United States market, and for other purposes.”

[lxxxii] See e.g., David N. Balaam and Bradford Dillman, “Introduction to International Political Economy,” 164.

Bibliography

Aklin, Michaël, Johannes Urpelainen, Patrick Bayer, and S. P. Harish. Escaping the Energy Poverty Trap: When and How Governments Power the Lives of the Poor. MIT Press, 2018.

Balaam, David N., and Bradford Dillman. Introduction to International Political Economy. 7th ed. New York, NY: Routledge, 2019.

Benoit, Philippe, and Kevin Tu. “Is China Still a Developing Country? And Why It Matters for Energy and Climate.” SIPA Center On Global Energy Policy. Columbia University, July 23, 2020. https://www.energypolicy.columbia.edu/research/report/china-still-developing-country-and-why-it-matters-energy-and-climate.

“BP Statistical Review of World Energy.” BP, 2019. https://www.bp.com/content/dam/bp/business-sites/en/global/corporate/pdfs/energy-economics/statistical-review/bp-stats-review-2021-full-report.pdf.

Chaurasiya, Prem Kumar, Vilas Warudkar, and Siraj Ahmed. “Wind Energy Development and Policy in India: A Review.” Energy strategy reviews 24 (2019): 342–357.

“China.” EnergyPolicyTracker.org. EnergyPolicyTracker.org, July 20, 2022. https://www.energypolicytracker.org/country/china/.

“China Headed towards Carbon Neutrality by 2060; President Xi Jinping Vows to Halt New Coal Plants Abroad.” United Nations. United Nations, September 21, 2021. https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1100642.

“China Rebuffs UK Criticism over Coal Move after Climate Summit.” Reuters. Reuters, November 15, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/business/cop/china-india-will-need-explain-coal-move-sharma-says-2021-11-14/.

Clark, Alex, and Weirong Zhang. “Estimating the Employment and Fiscal Consequences of Thermal Coal Phase-Out in China.” Energies (Basel) 15, no. 3 (2022): 800–.

“Company Profile.” China Southern Power Grid. Accessed July 14, 2022. http://eng.csg.cn/About_us/About_CSG/201601/t20160123_132060.html.

“Corporate Profile.” State Grid Corporation of China. Accessed July 14, 2022. http://www.sgcc.com.cn/html/sgcc_main_en/col2017112300/column_2017112300_1.shtml.

“Country Comparisons—Waterways.” Central Intelligence Agency. Central Intelligence Agency. Accessed July 25, 2022. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/field/waterways/country-comparison.

Delina, Laurence L. Accelerating Sustainable Energy Transition(s) in Developing Countries: The Challenges of Climate Change and Sustainable Development. Oxfordshire: Routledge, 2019. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.mutex.gmu.edu/lib/gmu/detail.action?docID=5108792&pq-origsite=primo.

Deng, Ke, and Ming Chen. “Blasting Excavation and Stability Control Technology for Ultra-High Steep Rock Slope of Hydropower Engineering in China: a Review.” European journal of remote sensing 54, no. sup2 (2021): 92–106.

“DFC Announces Approval to Provide up to $500 Million of Debt Financing for First Solar’s Vertically-Integrated Thin Film Solar Manufacturing Facility in India.” U.S. International Development Finance Corporation. U.S. International Development Finance Corporation, December 7, 2021. https://www.dfc.gov/media/press-releases/dfc-announces-approval-provide-500-million-debt-financing-first-solars.

“Energy Imports, Net (% Of Energy Use).” 2014. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.IMP.CONS.ZS?end=2014&locations=CN&most_recent_value_desc=true&start=1971&view=chart.

“Executive Summary – Enhancing China’s ETS For Carbon Neutrality: Focus On Power Sector – Analysis.” IEA, 2022. https://www.iea.org/reports/enhancing-chinas-ets-for-carbon-neutrality-focus-on-power-sector/executive-summary.

Fuyuno, Ichiko. “Japan and Vietnam Join Forces to Exploit Rare-Earth Elements.” Nature (London) (2012).

“Gross Domestic Product 2021.” The World Bank, July 14, 2022. https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GDP.pdf.

Guo, Rui. “China’s Communist Party Hits 96.7 Million, Boosted By Young And Educated.” South China Morning Post, June 30, 2022. https://www.scmp.com/news/china/politics/article/3183669/chinas-communist-party-grows-near-97-million-its-made-younger.

“How Much Electricity Is Lost in Electricity Transmission and Distribution in the United States?” U.S. Energy Information Administration. U.S. Department of Energy, July 13, 2022. https://www.eia.gov/tools/faqs/faq.php?id=105&t=3.

“H.R.6256 – To ensure that goods made with forced labor in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of the People’s Republic of China do not enter the United States market, and for other purposes.” Congress.gov. Library of Congress. Accessed July 27, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/6256.

Huang, Ping, Vanesa Castán Broto, and Linda Katrin Westman. “Emerging Dynamics of Public Participation in Climate Governance: A Case Study of Solar Energy Application in Shenzhen, China.” Environmental policy and governance 30, no. 6 (2020): 306–318.

Huaxia, ed. “Full Text of Xi’s Statement at the General Debate of the 76th Session of the United Nations General Assembly.” XinhuaNet. Xinhua, September 22, 2021. http://www.news.cn/english/2021-09/22/c_1310201230.htm.

“International Data: Direct Investment and MNE.” Bureau of Economic Analysis. U.S. Department of Commerce. Accessed July 18, 2022. https://apps.bea.gov/iTable/iTable.cfm?reqid=2&step=1&isuri=1#reqid=2&step=1&isuri=1.

“International Database.” United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. Accessed July 16, 2022. https://www.census.gov/data-tools/demo/idb/#/table?COUNTRY_YEAR=2022&COUNTRY_YR_ANIM=2022.

Jaganmohan, Madhumitha. “Leading countries in installed renewable energy capacity worldwide in 2021.” Statista, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/267233/renewable-energy-capacity-worldwide-by-country/.

Jing, Shuai, Leng Zhihui, Cheng Jinhua, and Shi Zhiyao. “China’s Renewable Energy Trade Potential in the ‘Belt-and-Road’ Countries: A Gravity Model Analysis.” Renewable energy 161 (2020): 1025–1035.

Keeley, Alexander Ryota, and Ken’ichi Matsumoto. “Relative Significance of Determinants of Foreign Direct Investment in Wind and Solar Energy in Developing Countries – AHP Analysis.” Energy policy 123 (2018): 337–348.

Ladislaw, Sarah, and Philippe Benoit. “Energy And Development: Providing Access And Growth.” CSIS, November 2017. https://csis-website-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/171127_Ladislaw_EnergyAndDevelopment_Web.pdf.

Li, Jiajia, Yucong Liu, Houjian Li, and Abbas Ali Chandio. “Heterogeneous Driving Factors of Carbon Emissions Embedded in China’s Export: An Application of the LASSO Model.” International journal of environmental research and public health 18, no. 19 (2021): 10423–.

Li, Xiaoyu, and Xilong Yao. “Can Energy Supply-Side and Demand-Side Policies for Energy Saving and Emission Reduction Be Synergistic?— A Simulated Study on China’s Coal Capacity Cut and Carbon Tax.” Energy policy 138 (2020): 1–14.

Lewis, Joanna I. “Toward a New Era of US Engagement with China on Climate Change.” Georgetown journal of international affairs 21, no. 1 (2020): 173–181.

Mallapaty, Smriti. “How China Could Be Carbon Neutral by Mid-Century.” Nature (London) 586, no. 7830 (2020): 482–483.

Pan, Xiongfeng, Shucen Guo, Cuicui Han, Mengyang Wang, Jinbo Song, and Xianchun Liao. “Influence of FDI Quality on Energy Efficiency in China Based on Seemingly Unrelated Regression Method.” Energy (Oxford) 192 (2020): 116463–.

Ritchie, Hannah, Max Roser, and Pablo Rosado. “China: Energy Country Profile.” Our World In Data, 2022. https://ourworldindata.org/energy/country/china.

“S.2463 — 115th Congress (2017-2018).” Congress.gov. Library of Congress. Accessed July 10, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/2463.

Shen, Wei, and Dong Jiang. “Making Authoritarian Environmentalism Accountable? Understanding China’s New Reforms on Environmental Governance.” The journal of environment & development 30, no. 1 (2021): 41–67.

Shi, Shuzhu, Ailing Hou, Yan Liu, Lei Cheng, and Zhiwei Chen. “Scattering Characteristics of Ultra-High-Voltage Power Lines in Spaceborne SAR Images.” Progress in electromagnetics research M Pier M 102 (2021): 13–26.

Statista Research Department, ed. “China: Electricity Transmission Losses 2021.” Statista, June 8, 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/302292/china-electric-power-transmission-loss/#:~:text=China’s%20power%20transmission%20losses%20amount,follows%20years%20of%20network%20improvement.

Tang, Haotian, Shu Zhang, and Wenying Chen. “Assessing Representative CCUS Layouts for China’s Power Sector Toward Carbon Neutrality.” Environmental science & technology 55, no. 16 (2021): 11225–11235.

Tu, Qiang, Jianlei Mo, Regina Betz, Lianbiao Cui, Ying Fan, and Yu Liu. “Achieving Grid Parity of Solar PV Power in China- The Role of Tradable Green Certificate.” Energy policy 144 (2020): 111681–.

Wang, Peng, Muyi Yang, Kristy Mamaril, Xunpeng Shi, Beibei Cheng, and Daiqing Zhao. “Explaining the Slow Progress of Coal Phase-Out: The Case of Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Region.” Energy policy 155 (2021): 112331–.

Xie, Bai-Chen, Jie Gao, Yun-Fei Chen, and Na-Qian Deng. “Measuring the Efficiency of Grid Companies in China: A Bootstrapping Non-Parametric Meta-Frontier Approach.” Journal of cleaner production 174 (2018): 1381–1391.

Xie, Bai-Chen, Kang-Kang Ni, Eoghan O’Neill, and Hong-Zhou Li. “The Scale Effect in China’s Power Grid Sector from the Perspective of Malmquist Total Factor Productivity Analysis.” Utilities policy 69 (2021): 101187–.

Xu, Lingjun, Da Sang, and Xiaohu Zhang. “Analysis of Influence of Large-Scale External Power on East China Power Grid.” IOP conference series. Earth and environmental science 514, no. 4 (2020): 42026–.

Xu, Muyu, and John Geddie.”Analysis: To Tackle Climate Change, China Must Overhaul Its Vast Power Grid.” Reuters, May 19, 2021. https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/tackle-climate-change-china-must-overhaul-its-vast-power-grid-2021-05-19/.

Yang, Fang, Sheng Zhang, and Chuanwang Sun. “Energy Infrastructure Investment and Regional Inequality: Evidence from China’s Power Grid.” The Science of the total environment 749 (2020): 142384–142384.

Zaretskaya, Victoria, and Faouzi Aloulou. 2022. “As Of 2021, China Imports More Liquefied Natural Gas Than Any Other Country”. Energy Information Administration. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=52258.

Zhang, Jing. “Oil and Gas Trade Between China and Countries and Regions Along the ‘Belt and Road’: A Panoramic Perspective.” Energy policy 129 (2019): 1111–1120.

Zhou, Lihuan, Sean Gilbert, Ye Wang, Miquel Muñoz Cabré, Kevin P. Gallagher, Moving the Green Belt and Road Initiative: From Words to Actions. Washington, DC: World Resources Institute, 2018. https://www.bu.edu/gdp/files/2018/11/GDP-and-WRI-BRI-MovingtheGreenbelt.pdf.

Zhou, Weihuan, Qingjiang Kong, and Huiqin Jiang. “Technology Transfer Under China’s Foreign Investment Regime: Does the WTO Provide a Solution?” Journal of world trade 54, no. 3 (2020): 455–.

“9.1. Base Load Energy Sustainability.” EME 807: Technologies for Sustainability Systems. Pennsylvania State University. Accessed July 26, 2022. https://www.e-education.psu.edu/eme807/node/667.

Image: Wikipedia