By: Ryan Carver, GMU Student Contributor

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The stated goal of this research paper is to increase clean energy access and improve climate resilience for the nation of Vietnam. Vietnam’s socialist oriented market economy, bountiful natural resources, and current coal-centric energy mix provides a unique opportunity to enact energy policy changes. Vietnam’s diplomatic and trade relations with the U.S. can be further strengthened by U.S. policy actions (with the goal of promoting a clean energy transition), such as: providing technical assistance to improve energy transmission losses and to help establish a one-stop-shop licensing agency for clean energy projects, and funding Vietnam’s rare earth research center to improve U.S. supply chains of rare earth resources. The Vietnamese can take action to close the 300+ billion USD funding gap required to transition the nation to clean energy use (by 2040) by: establishing carbon sinks to sell carbon credits on the global market, redirecting fossil fuel subsidies to clean energy projects, strengthening purchasing power agreements between the national energy provider (EVN) and international energy suppliers, and increasing the current carbon tax rate. Without these policy actions, Vietnam has no chance of meeting its 2050 carbon neutral goal, and it will face the consequences of climate change without sufficient funding to combat them.

Introduction

Vietnam and its energy sector are in a precarious position, with the nation’s economic “development affected by climate change” in a very startling way.1 It is expected that Vietnam could see a loss of up to “16% of GDP a year by 2050” due to the results of climate change and the impact of greenhouse gas emissions (GHG).1 To achieve a state of “climate-resilience” and meet the Vietnamese government’s stated goal of reaching “net zero emissions” by 2050, it is expected that the nation will need additional investment totaling “$368 billion U.S.D. through 2040.”1This is a staggeringly large number, and to reach it will require a herculean effort by the government of Vietnam, its “domestic private sector,” public and private external financiers, and U.S. foreign aid assistance.

There are a number of actions that the Vietnamese government can take to help shrink this gap in funding for its clean energy transition, such as: increasing carbon tax rates, setting up a singular energy licensing and permitting agency to promote foreign direct investment (FDI), redirect fossil fuel subsidies to clean energy projects, working to set up carbon sinks in protected forestland to generate carbon credit revenues, and strengthening purchasing power agreements and feed-in tariffs for clean energy projects to encourage increased FDI. Considering our nation’s diplomatic and trade relations with Vietnam, it would also be in our interest to help Vietnam mitigate the imminent effects of climate change, both for national security, trade, and climate reasons that will be discussed in detail later in this paper. To help the Vietnamese meet these clean energy financing goals, it is the role of the U.S. to: contribute increased funding for clean energy projects, provide technical assistance with existing grid modernization and transmission loss prevention, provide political science expertise to the Vietnamese to encourage the creation of a one-stop-shop clean energy project permitting agency, and invest in Vietnam and Japan’s joint “Rare Earth Research and Technology Transfer Centre” to strengthen the U.S. supply chain of rare earth materials and to help Vietnam access and sell its valuable natural resources to increase funding for its clean energy transition.

Background

Economy and Population Statistics

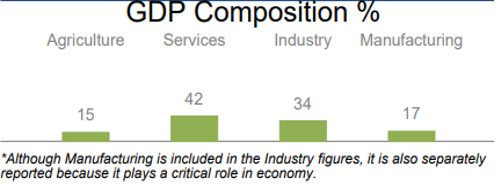

Vietnam has a population of approximately 99 million and is classified as having a “mixed socialist-oriented market economy.” The government of Vietnam (the Socialist Republic of Vietnam) ratified its constitution in 1992, with the “focus on strict communist orthodoxy” becoming “less important than economic development as a national priority” as time has progressed.2 This is a rather unique situation amongst communist nations, as the government is still socialist in its approach to governance but is open to liberalizing its markets to encourage more economic prosperity and GDP growth.2 This unique political situation has done wonders for Vietnam’s economic growth (despite its developing nation status), with a yearly GDP of 362.64 billion and an annual GDP growth rate of 2.6%.3 The “life expectancy at birth” for a Vietnamese citizen is 75, and the nation has a 0.7/1.0 Human Capital Index Score, placing Vietnam as a developing nation with room to grow and improve in terms of human flourishing and access to capital.3 Vietnam has a fairly diverse economy, as can be seen from the GlobalEDGE chart below.6 The diversity of GDP composition is promising here, but that agriculture output of 15% is mainly occurring in the coastal regions of Vietnam. As discussed in the introduction, by 2050 it is expected that Vietnam will see a 16% drop in its GDP mostly resulting from rising sea levels that will flood these agriculturally rich areas1.

Retrieved from GlobalEDGE6

The national currency of Vietnam is the Vietnam Dong (VDN), the value of which is approximately $1 USD to 23,448 VND.3 The State Bank of Vietnam manages the VND “through a crawling peg to the U.S. dollar,” 4 meaning that the VND is a currency with a “fixed exchange rate that is allowed to fluctuate within a band of rates.”4 This strategy for managing currency can have a negative impact on international investor desire to do business and make investments in local currency, which can be seen in Vietnam’s struggles to attract investors willing to do business using the VND. This can partly be understood by looking at the World Bank “Ease of Business” report from 2019 that ranks Vietnam as 70 out of 190 countries listed; there is clearly quite a bit of improvement for the government to make to ensure that activities like “starting a business” become easier.5 If Vietnam can make business easier to conduct within its borders, it would help ensure a more substantial flow of FDI and increase opportunities for public-private partnerships in various sectors of the economy (but most importantly in the energy sector).5

Energy Profile

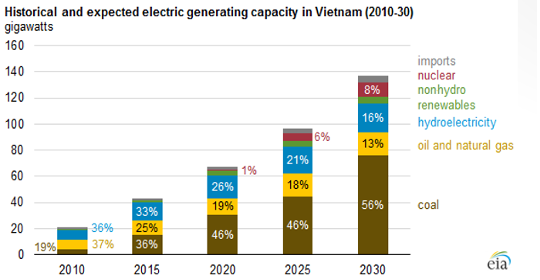

Vietnam is an incredibly resource rich nation. The nation has 3,444km of coastline, 47.2% of its land is forested, and it is approximated that it has rare earth reserves exceeding 22 million tons, making Vietnam the nation with the second most rare earth resources (behind China).7 Vietnam has been able to position itself as an “important oil and natural gas producer in Southeast Asia,” but at the cost of being a “net importer of refined oil products.”7 Given that the nation’s oil consumption doubled “in the decade between 2006 and 2016,”7 and “Vietnam’s coal use in the last five years grew 75%” (faster than any nation on Earth)8, the Vietnamese goal of carbon neutrality by 2050 is a complete pipe-dream given the current policy environment and lack of investment for clean energy projects as well as the subsidizing of the fossil fuel industry. Vietnam has moderate fuel reserves by southeast Asian standards, with approximately 4.4 billion barrels of crude oil reserves, ~30 trillion cubic feet of natural gas reserves, and approximately 10.5 billion metric tons of coal reserves.7 So, what can these reserves tell us about Vietnam’s energy mix? Vietnam is increasingly relying on coal imports to “meet rapidly increasing electricity demand,” with “more than half of Vietnam’s electricity generation” coming from coal in 2020 alone.10 Vietnam also relies significantly on hydroelectric power generation, with 26% of its “generation share” coming from hydro power that is unreliable due to “periodic droughts and water shortages”.7 This reliance on coal to meet increasing energy demand could be considering a drop in the bucket in terms of global emissions, but it leaves Vietnam locked-in to using coal and in a dangerous position should the price of imported coal dramatically increase.

Retrieved from U.S. EIA10

In terms of electricity generation, Vietnam is lagging far behind where it needs to be to meet increasing demand. In 2021, Vietnam only generated approximately 250 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity11, and the projected demand for the nation in 2030 is between 572 and 632 TWh. Electricity generation per capita per year is approximately 2,300 kilowatt-hours (KWh) in Vietnam; compare that to the 10,000 plus KWh generated per capita in developing nations like the U.S. or Canada, and it’s easy to understand just how far behind in generation Vietnam really is. Without a major ramping up of electricity generation from clean energy sources coupled with improvements in transmission losses, there will continue to be a large gap between the demand and supply of energy.

Escaping the Energy Poverty Trap

Vietnam reached 100% electrification around 2011, but “41 percent of Vietnamese households continue to lack access to modern cooking fuels.”9 This effort to electrify the entire country (with an intense focus on rural electrification projects) stems from the government’s need to “secure regime legitimacy through agricultural and industrial growth” following the end of its war with the U.S.9 Michael Aklin’s book “Escaping the Energy Poverty Trap” gives us a good framework to better understand the importance of local accountability, political will, and institutional capacity for reducing energy poverty in Vietnam.

Local Accountability

In the case of the Vietnamese authoritarian government system, there was (and is) a strong level of local accountability when it came to the rollout and execution of the rural electrification strategy for the nation. There was as high level of “local authorities’ responsiveness to strong local accountability,” meaning individual citizens and local regulators kept the national government in check when it came to meeting their promised electrification targets.9 The “last-mile distribution responsibilities” to improve rural energy access fell to local authorities and citizens, meaning that the “willingness of local communities to contribute to the program” was essential to getting the nation electrified.9

Political Will

Given that the “government’s interest in rural electrification was strong and stemmed from the need to secure regime legitimacy,” it is fair to suggest that the political will to improve the energy system in Vietnam is quite high even to this day. The “rural electrification boom” only occurred “once the central government began making public investments,” and while public investment cannot replace FDI and external funds for Vietnam in 2022, it is still important to remember that the government must have a vested interest in energy policy solutions for them to take hold and remain relevant.9 If the legitimacy of your political party is dependent on keeping the cost of energy low and improving the economy every year, it stands to reason that you would do everything in your power to keep those things true.

Institutional Capacity

Vietnam has a rigid “hierarchical structure for rural electrification,” and this is mostly thanks to the development of a “capable power sector administrator” at the national level that was able to work with regional authorities to carry out its rural electrification plans.9 Electricity Vietnam (EVN), the national power provider with monopoly power over the energy market, was able to “improve capacity” and “decrease transmission and distribution losses” by directly overseeing regional energy implementation in concert with regional energy groups. By ensuring the “technical quality of the rural energy networks,” EVN and the national government were able to leverage their institutional capacity and top-down government power structure to create a “commercially sustainable” and scalable rural energy program that resulted in 100% electrification for the nation.9

The Policy Environment, the Energy Market, and FDI Determinants

On the topic of the EVN, its important to understand the players in the Vietnamese energy market. The EVN is a “state-owned enterprise that reports directly to the Prime Minister,” it is the “largest buyer of electricity” in the nation, and it has a “monopoly on transmission and distribution” of energy.12 Independent power producers (IPPs) do operate in Vietnam, but mainly as a way for the government to shift a “large portion of the investment in the power generation sector” onto outside entities and investors.12 The allowance of IPPs was a strategy by the government and EVN to close the gap between operating costs for Vietnam’s “73 power plants” and the limited funds available from “self-financing and other sources of debt financing.”12 As such, these IPPs are only given limited room to operate within the energy sector, and to this point only one U.S. company (AES Corporation) has been willing to act as an IPP in Vietnam due to the government’s strict monopoly over the “electricity transmission grid.”12 EVN’s transmission infrastructure is also “struggling to keep pace with the rapid capacity growth,” and this is in part due to the rise in the use of renewable energy and difficulties with grid integration12. EVN also struggles with grid efficiency and transmission loss issues, with the self-reported “power loss rate of 6.5%” likely being a vast under exaggeration of the rampant problems with “the development of the power grid” not keeping up with the growth of demanded energy load.13

On top of the issues presented by EVN’s monopoly over the energy sector in Vietnam, the policy environment of Vietnam can be complicated to navigate, and often deters potential FDI opportunities that the nation desperately needs. The IUCN produced a report about vital determinants for attracting FDI for clean energy projects, and in that report, they identify institutional and macroeconomic environments, natural conditions, and renewable energy policies to be some of the most important areas that potential investors are thinking about for investment opportunities abroad.14 Of this broad set of determinants, four stand out as the most essential for Vietnam to address to attract the hundreds of billions need in FDI to fund a clean energy transition: political risk, administrative procedure, exchange rate volatility, and feed-in tariffs.14 For political risk (as has been previously established), the communist party of Vietnam’s hold on national power is not guaranteed in times of economic upheaval or stagnant economic growth. This could potentially lead to a change in political parties, which could result in widespread upheaval or internal conflict, hence why investors would be worried about this determinant. For administrative procedures, the complex bureaucracy and government-operated energy sector can create headaches for potential investors or developers when it comes to gaining licenses and permits to construct or improve energy infrastructure. For exchange rate volatility and feed-in tariffs, the same logic applies: make it hard for investors to do business in your currency (in this case, by pegging the Vietnam Dong to the USD) and disincentivize investment in clean energy projects by not establishing feed-in tariffs to subsidize the cost of renewable energy generation, and you can expect to receive little to no FDI for clean energy projects.

Literature Review and Analysis

Nguyen, Trinh, et.al. (2017), “Market Conditions and Change for Low Carbon Electricity Transition in Vietnam”

As Vietnam has slowly transitioned “from a planned to a market economy,” there has been a constant challenge with energy security for the nation.15 Vietnam has locked itself in to using fossil fuels, given that “by 2030, coal-fired power stations are expected to account for 53.2 percent of installed capacity.”15 Vietnam is subject to “strong path dependencies” when it comes to constraining the “structures and rules” of the “distribution of economic rents” due to the concentration of political and economic power in the national government.15 The current “institutional framework” of Vietnam is hampering the “development of renewables,” given that there are players in the government that have a vested interest in implementing policy that rewards the fossil fuel industry.15 On top of these vested interests, you also have “counter-incentives for renewables” in play such as renewable energy costs, “operation and management” costs for renewable project construction, and high initial investment cost to scale renewables and get them integrated with the existing power grid.

Nguyen, Trung Thanh, et.al. (2019), “Energy Transition, Poverty and Inequality in Vietnam”

The General Statistics Office of Vietnam (GSC) conducts a “Household Living Standards Survey” every two years, and the authors used the results of this survey to determine: how rampant energy poverty still is in Vietnam, how much access citizens currently have to “clean energy,” and how likely the Vietnamese government is to adopt and scale clean energy projects in rural areas of the nation.16 On the first point of interest, there is still an issue with energy poverty for many rural citizens that are living in a “low income high energy cost” situation.16 Given that many rural households have a “per capita disposable income” of less than 60% of the “national median income,” there is still rampant energy poverty in rural areas of Vietnam, despite the 100% electrification rate achieved by the nation around 2011.16 As these citizens are dealing with the implications of poverty, they will turn to “coal and biomass expenditures” as their main source of household energy consumption, meaning that the “poorest proportion of ethnic minorities” are forced to use unclean energy due to a lack of subsidized cost for renewables.16 Given that reducing energy poverty “has not been considered an important policy agenda,” and that the government’s focus has been solely on increasing access to electricity, it is clear that there are few plans to scale clean energy projects in rural areas of Vietnam to help address these issues.16

David Dapice (2018), “Vietnam’s Crisis of Success in Electricity.”

The focus of this research is to analyze “the cost of the variety of power generation systems” that can lead Vietnam to having a “successful energy mix,” and it is divided into three main sections: “efficiency and use,” “coal vs gas,” and “renewables.”8 On the issues of efficiency and energy use, Vietnam has seen an “annual growth rate of electricity demand” of 12%, which is outpacing “any other comparable Asian economy” and indicates that “Vietnam uses electricity too inefficiently.”8 Given that the price of electricity has continuously fallen for consumers, it is clear that energy is being priced “below the cost of new production and its delivery,” leading to issues for Vietnam’s energy sector when it comes to energy grid upgrades and the lack of funds available to the government for upkeep of the grid.8 Given that “coal use in the last five years grew 75%” despite the resource being “imported and facing intense political resistance due to local pollution concerns,” it is clear that the Vietnamese government has prioritized fixing its lagging energy supply by importing coal rather than utilizing their “ample offshore domestic” natural gas reserves.8 This is in part due to the government taxing “domestic gas production” very heavily and EVN claiming that it is “dangerously unreliable” to rely on natural gas instead of coal for baseload energy production.8

Policy Recommendations

U.S. | FDI and Technical Assistance for: Clean Energy Project Licensing Agency, Grid Modernization, and Transmission Loss Prevention

The U.S. already provides extensive technical assistance to the Vietnamese government through programs like the USAID Vietnam Urban Energy Security or Low Emissions Energy Program but has not to this point tried to assist the government with setting up a singular licensing agency that would cut down on administrative headaches associated with starting a clean energy project in Vietnam. By lending technical and political science assistance to aid in the creation of this permitting agency, the U.S. would be making it easier for international investors to gain access to the permits and licenses needed to operate in the socialist markets of Vietnam, thereby lowering the perceived risk for developing a clean energy project in the country. Similarly, the state controlled EVN could use training and technical assistance with grid modernization and transmission loss prevention to improve the efficiency of current electricity production. By contributing FDI and technical assistance specifically for the purpose of improved transmission losses, the U.S. also helps Vietnam tamp down on its growing coal use, meaning that the EVN can provide cheap energy to its consumers for the same cost as before but now with less transmission losses eating at the profit margins.

U.S. | Fund Vietnam and Japan’s “Rare Earth Research and Technology Transfer Centre”

While the U.S. cannot partner directly with Vietnam and Japan to promote rare earth research due to geopolitical implications with China, it is in its interest to create a stable supply chain of rare earth resources for use in clean energy projects. Currently, the U.S. is reliant on China for most of it’s supply of rare earth materials, and the supply chains for these materials are inefficient and don’t meet perceived demand in the U.S. market. If the U.S. helps to fund this technology transfer center, it will have a twofold impact: it would help Vietnam access and sell its vast rare earth resources to help fund its clean energy transition, and it would ensure that the U.S. is at the front of the line to buy Vietnamese rare earth materials when they become more readily available on international markets.

Vietnam | Increase Carbon Tax Rates

The Vietnamese government has currently capped its tax on carbon at ~$15 USD per ton. The willingness to establish a carbon tax in the first place indicates that the government understand the revenue potential of a carbon tax as well as the positive environmental impact of such a tax. By increasing that carbon tax cap to $30 a ton by 2030, and approximately $90 a ton by 2040, the government of Vietnam would generate over $80 billion USD in revenue over the next 18 years.8 This would do a significant amount to close the funding gap for Vietnam to be sufficiently climate resilient and focused on clean energy production and integration with the existing grid.

Vietnam | Redirect Fossil Fuel Subsidies to Clean Energy Projects, and Strengthen PPAs and Feed-in Tariffs to Attract FDI

The Vietnamese government currently subsidizes the fossil fuel industry (through direct cash payments to citizens) to keep the cost of energy low, but these subsidies are negatively impacting the development and integration of clean energy projects in the nation. By redirecting the 280+ million USD in subsidies for fossil fuels to clean energy project development and integration, the government wouldn’t be spending more on energy subsidization and they would be simultaneously signaling to international developers that clean energy is a preferred part of the energy mix for Vietnam. Along those same lines, EVN’s PPAs with international power supplies need to be strengthened to ensure investors that they will have priority access to the grid and that they will be able to sell energy to EVN for a guaranteed term at a guaranteed price. The same goes for the re-establishment of feed-in tariffs to encourage more clean energy projects (mainly solar); these tariffs had a tremendous effect on attracting solar project developers to Vietnam until they were ceased in 2019, so the nation already has a model of success to reinstitute.

Vietnam | Allow More Regions to set-up Carbon Sinks, Sell Carbon Credits

Given Vietnam’s vast amount of forested land, it is logical that the nation would undergo a concerted effort to set up carbon sinks and sell carbon credits on the global market. The Vietnamese province of Quang Nam is the first province to request government permission to establish carbon sinks on land conserved by the national government, and it is expected that the province will be able to sell “6 million carbon credits for about 30 million USD by 2025.”17 If the national government were to assess its forest resources and work in concert with all its provinces to determine the viability of establishing carbon sinks, there is a huge opportunity for revenue generation that can help the nation become more climate resilient and allow for more government investment in a clean energy transition.

Bibliography

- Retrieved from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/37618/Vietnam%20REVISED.pdf?sequence=18

- World Bank (2022), “Key Highlights: Country Climate and Development Report for Vietnam.” Retrieved from: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/brief/key-highlights-country-climate-and-development-report-for-vietnam

- https://data.worldbank.org/country/VN

- World Bank (2019), “Ease of Doing Business.” Retrieved from: https://archive.doingbusiness.org/en/rankings

- GlobalEdge (2022), “Vietnam: Government.” Retrieved from: https://globaledge.msu.edu/countries/vietnam/government

- Investopedia (2020), “VND (Vietnam Dong).” Retrieved from: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/forex/v/vnd-vietnamese-dong.asp#:~:text=VND%20is%20managed%20by%20the,must%20always%20specify%20Vietnamese%20%C4%91%E1%BB%93ng.

- GlobalEdge (2020), “Vietnam Memo.” Retrieved from: https://globaledge.msu.edu/countries/vietnam/memo#:~:text=Vietnam%20has%20a%20mixed%20economy,%2DPacific%20Partnership%20(TPP).

- David Dapice (2018), “Vietnam’s Crisis of Success in Electricity.” Harvard Kennedy School. Retrieved from: https://ash.harvard.edu/files/ash/files/1.4.19_english_david_dapice_electricity_paper.pdf

- Aklin Michaël, Johannes Urpelainen, Patrick Bayer, and S. P. Harish. Escaping the Energy Poverty Trap: When and How Governments Power the Lives of the Poor. MIT Press, 2018.

- Retrieved from: https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=48176

- Our World in Data (2022), “Vietnam Data.” Retrieved from: https://ourworldindata.org/country/vietnam#search=electricity-access

- International Trade Administration (2021), “Vietnam: Power Generation, Transmission, and Distribution.” Retrieved from: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/vietnam-power-generation-transmission-and-distribution

- EVN, “Vietnam’s power loss ratio is close to the technical threshold” (2020). Retrieved from: https://en.evn.com.vn/d6/news/Vietnams-power-loss-rate-is-close-to-the-technical-threshold-66-163-1836.aspx#:~:text=EVN’s%20member%20organizations%20have%20implemented,2018%20and%206.5%25%20in%202019.

- IUCN (2022), “Unlocking International Financing for Vietnam’s Renewable Energy Transition.” Retrieved from: https://www.iucn.org/news/viet-nam/202205/unlocking-international-finance-vietnams-renewable-energy-transition

- Nguyen, Trinh, et.al. (2017), “Market Conditions and Change for Low Carbon Electricity Transition in Vietnam,” The Journal of Energy and Development, 2017 ,Vol. 43, no. ½, p. 1-26. Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26539566?seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents

- Nguyen, Trung Thanh, et.al. (2019), “Energy Transition, Poverty and Inequality in Vietnam,” Energy Policy, September 2019, Vol. 132, pp. 536-548. Retrieved from: https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0301421519303714?token=720F2B64FFDEDC00F80B5CF3CDE1511BB7079CFC0F7045A15AD33AFF99FDA030383348FDEF3612FE78996A1C8193FCC8&originRegion=us-east-1&originCreation=20220727115838

- VietnamPlus (2022), “Vietnam Takes Steps Toward Carbon Credit Market.” Retrieved from: https://en.vietnamplus.vn/vietnam-takes-steps-towards-carbon-credit-market/223938.vnp#:~:text=It%20was%20estimated%20that%20Vietnam,up%20to%201.25%20million%20cu.

Image: ecovis.com